Understanding foodborne pathogens is critical for anyone in the food industry. Each year, contaminated food makes about 1 in 10 people worldwide sick, roughly 600 million cases and causes 420,000 deaths. In the U.S., six major pathogens account for nearly 10 million illnesses and over 53,000 hospitalizations annually.

Moreover, the economic impact is enormous: unsafe food costs an estimated $110 billion per year in lost productivity and healthcare. For food companies, even a single outbreak can cost millions in recalls and damage their brand’s reputation. In our global supply chain, contamination in one region can reach consumers everywhere.

For you as a food processor or safety manager, these facts underscore why proactive pathogen control (via sanitation, monitoring, and training) is essential. In this guide, we’ll cover the most important pathogens, how they spread, and best practices you can apply to keep your facility and products safe.

What Are Foodborne Pathogens?

Foodborne pathogens are harmful microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, and toxins that contaminate food and cause illness when consumed. These pathogens are responsible for a significant number of foodborne diseases worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), unsafe food containing harmful bacteria, viruses, parasites, or chemical substances causes more than 200 diseases, ranging from diarrhea to cancer.

Categories of Foodborne Pathogens

- Bacteria: Single-celled organisms that can multiply rapidly in favorable conditions. Common examples include Salmonella, Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Listeria monocytogenes.

- Viruses: Smaller than bacteria and require a living host to replicate. Norovirus and Hepatitis A are notable examples.

- Parasites: Organisms that live on or inside a host. Toxoplasma gondii and Trichinella are examples that can be transmitted through undercooked meat.

- Toxins: Poisonous substances produced by certain bacteria, such as Clostridium botulinum, which cause botulism

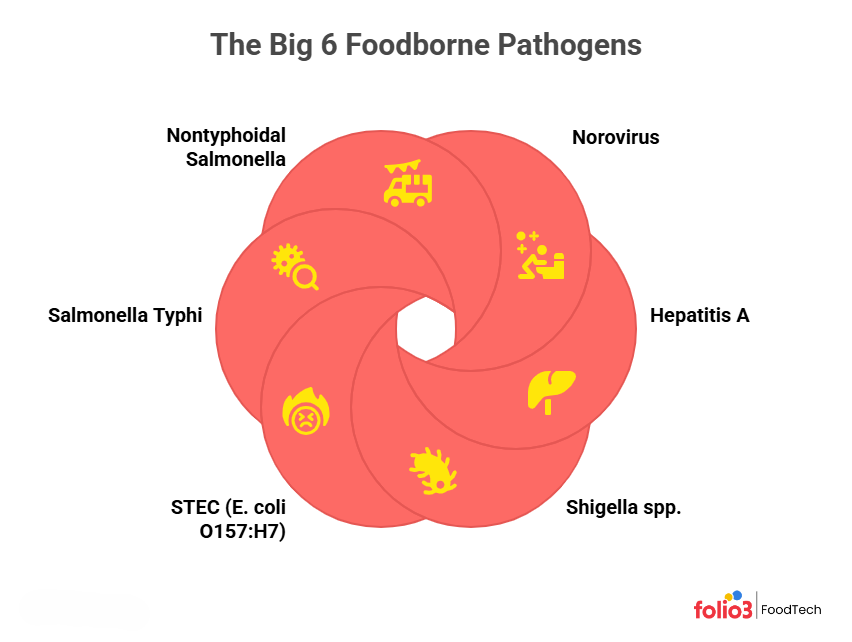

The Big 6 Foodborne Pathogens: A Closer Look

The FDA and CDC highlight six pathogens as especially hazardous in foodservice and RTE (ready-to-eat) settings. These “Big 6” can cause severe illness even from low doses. Below, we define each and give key facts:

1. Norovirus

A highly contagious virus causing acute gastroenteritis.

- Sources: Contaminated shellfish, fresh produce, or any food handled by an infected person. The virus also spreads easily on surfaces and via person-to-person contact.

- Symptoms: Sudden vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, and cramps 12–48 hours after exposure. Illness usually lasts 1–3 days; dehydration is the main risk.

- At-Risk: All ages can get norovirus; young children, older people, and immunocompromised individuals are most vulnerable to severe dehydration. A single sick worker can infect many customers.

- Prevention: Rigorous handwashing (20 seconds with soap) and surface sanitation are critical. Exclude sick employees for at least 48 hours after symptoms. Cook shellfish thoroughly and wash produce well. In outbreaks, use bleach-based disinfectants on surfaces.

2. Hepatitis A

A liver-infecting virus spreads via the fecal-oral route. It often enters food through contaminated water or an infected food handler.

- Sources: Outbreaks often stem from raw/undercooked shellfish, fresh produce (berries, salads), or any ready-to-eat food handled by an infected person. Unchlorinated water also poses a risk.

- Symptoms: After ~15–50 days, symptoms include fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and jaundice (yellow eyes/skin). Fever and dark urine can occur. Young children often show mild or no symptoms but can still spread the virus.

- At-Risk: Anyone without immunity (no prior infection or vaccine) can be infected. Severity rises with age or pre-existing liver disease. Food handlers are a key risk – one asymptomatic worker can contaminate many meals.

- Prevention: Vaccinate food workers and travelers against Hepatitis A. Enforce strict hand hygiene and glove use, and exclude any ill staff. Sanitize food-contact surfaces. Thoroughly wash produce and cook shellfish.

3. Shigella spp.

Bacteria causing shigellosis (bacillary dysentery). Extremely infectious and spread via fecal contamination.

- Sources: Foods touched by contaminated water or handlers – raw salads, leafy greens, and unwashed produce often trigger outbreaks. Very few organisms (10–100) can infect a person.

- Symptoms: Frequent bloody diarrhea, fever, and cramps starting ~1–2 days after exposure. Illness lasts about a week.

- At-Risk: Young children (daycares), travelers, and immunocompromised individuals are most vulnerable. Everyone can be sickened, though.

- Prevention: Enforce handwashing (especially after the restroom) and safe restroom practices. Keep raw and ready-to-eat foods separate. Cooking kills Shigella, so focus on preventing initial contamination and ensuring utensils and surfaces stay clean.

4. STEC (E. coli O157:H7)

Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli that causes severe disease.

- Sources: Undercooked ground beef, raw milk/cheese, and contaminated produce (spinach, sprouts) are standard vehicles. These foods can pick up animal feces. In the U.S. STEC causes an estimated 265,000 infections/year.

- Symptoms: Severe stomach cramps and often bloody diarrhea 2–5 days after eating. Vomiting is common. Most recover in about a week, but young children and the elderly risk hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), a dangerous kidney failure.

- At-Risk: Young children (<5 years) and older adults face the highest risk of HUS. Others (immune-compromised, pregnant) can have severe disease too.

- Prevention: Cook ground beef thoroughly (≥160°F) and avoid raw milk/juice. Wash all produce carefully. Prevent cross-contact of raw meat with ready-to-eat foods. Rapidly refrigerate leftovers (avoid “danger zone” holding) to limit E. coli growth.

5. Salmonella Typhi

Salmonella Typhi causes typhoid fever, a severe systemic illness. It is human-specific and rare in the U.S. but common where sanitation is poor.

- Sources: Contaminated food or water (via sewage). Any uncooked item washed or handled with tainted water (salads, raw vegetables) can transmit Typhi. In endemic areas, food prepared by a chronic carrier is also a source.

- Symptoms: After ~1–3 weeks, causes high fever, headache, abdominal pain, and sometimes a rash of “rose spots”. Gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation can occur if untreated. Typhoid fever requires prompt antibiotic treatment.

- At-Risk: Travelers to typhoid-endemic regions (Asia, Africa, Latin America) are at the highest risk. Unvaccinated persons (especially young) face the greatest danger.

- Prevention: Vaccinate food handlers and travelers to high-risk areas. Ensure safe water (bottled or boiled) and hygiene abroad. In your facility, provide only potable water and enforce strict handwashing.

6. Nontyphoidal Salmonella

Common Salmonella serotypes (e.g., Enteritidis, Typhimurium) cause salmonellosis.

- Sources: Many foods can carry Salmonella. Raw/undercooked poultry, eggs, meats, and raw milk are classic sources. Produce (melons, leafy greens) or spices have also triggered outbreaks. The bacteria survive well, so that cooked foods can be contaminated by raw drips.

- Symptoms: Diarrhea (sometimes bloody), fever, and abdominal cramps 6–72 hours after exposure. Symptoms last 4–7 days. Dehydration is the main risk; most recover without treatment.

- At-Risk: Babies, the elderly, and immunocompromised persons may develop severe illness (sometimes bloodstream infection). Otherwise healthy people usually recover fully.

- Prevention: Cook poultry to 165°F (or 145–160°F for other meats). Refrigerate eggs and dairy; avoid raw milk. Prevent raw/cooked food cross-contamination and clean kitchen tools and surfaces thoroughly.

Other Common Foodborne Pathogens to Watch

Even beyond the Big 6, several other common food pathogens continue to cause costly recalls and outbreaks worldwide. So, it is essential to understand these too for strengthening your food safety systems and protecting both your consumers and your brand.

Campylobacter Jejuni

Campylobacter jejuni is a bacterial pathogen that causes gastroenteritis.

- Sources: Raw or undercooked poultry, unpasteurized milk, or contaminated water.

- Symptoms: Fever, diarrhea (often bloody), and cramps 2–5 days after exposure. Illness lasts about a week.

- Prevention: Cook poultry to 165°F, avoid raw milk, and sanitize surfaces/utensils after handling raw meat.

Listeria Monocytogenes

A bacterium that can grow at refrigeration temperatures, causing listeriosis.

- Sources: Ready-to-eat deli meats, hot dogs, soft cheeses, smoked seafood, and produce can be contaminated.

- Symptoms: Fever, muscle aches, and sometimes diarrhea. In severe cases (especially in pregnant women), it causes meningitis or bloodstream infection. Pregnant women risk miscarriage.

- Prevention: Eliminate or heavily process high-risk foods for vulnerable groups. In manufacturing, run regular environmental monitoring and rigorous sanitation. Keep RTE foods cold and handle them under strict hygienic conditions to prevent any Listeria growth.

Clostridium Perfringens

Clostridium botulinum produces botulinum toxin, causing large outbreaks.

- Sources: Foods held warm (60–120°F) like gravies, stews, and large meat dishes. Spores survive cooking and germinate if cooling is slow.

- Symptoms: Abdominal cramps and diarrhea 8–16 hours after eating. Illness typically lasts about 24 hours.

- Prevention: Cook and reheat foods thoroughly, and cool leftovers quickly (use shallow pans or ice baths). Keep hot foods above 135°F and never leave large batches at room temperature.

Clostridium Botulinum

A spore-forming bacterium producing a potent neurotoxin, causing botulism.

- Sources: Improper home-canned or preserved foods (low-acid vegetables, meat, fish). Honey can contain spores and cause infant botulism.

- Symptoms: 12–36 hours after ingestion: blurred vision, drooping eyelids, difficulty swallowing, and paralysis. This can lead to respiratory failure if untreated.

- Prevention: Do not eat from bulging or damaged cans. Boil home-canned foods 10 minutes before tasting (heat destroys toxins). Do not feed honey to infants under 1 year. Use proper pressure-canning techniques for low-acid foods.

Vibrio Spp.

It is bacteria that live in warm seawater, including V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus.

- Sources: Raw or undercooked seafood (especially oysters). Seawater contact can also infect open wounds.

- Symptoms: Diarrhea, vomiting, and cramps. V. vulnificus can also cause severe bloodstream infections with high mortality in high-risk patients.

- Prevention: Cook all seafood thoroughly (especially shellfish). Prevent cross-contamination with raw seafood. Keep seafood chilled and use clean (potable) water for ice and washing. Cover any open cuts when handling seafood or swimming in seawater.

Bacillus Cereus

A bacterium causes two forms of food poisoning, typically resulting in nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Sources: The emetic (vomiting) form comes from rice, pasta, or starchy foods left at room temperature. The diarrheal form comes from meats, sauces, or vegetables left too long.

- Symptoms: Emetic vomiting (1–5 hours after eating) and diarrheal, watery diarrhea and cramps (6–15 hours after). Both are usually brief (~24 hours).

- Prevention: Cool cooked rice, pasta, and other starches promptly and refrigerate. Reheat only once to steaming. Discard foods left at room temperature beyond 2 hours. Maintain hot foods above 140°F and cold foods below 40°F.

Common Transmission Routes and Risk Factors for Pathogens in Food

Understanding how pathogens enter the food chain is key to blocking them. Major risk factors include:

Improper food handling

Mistakes like leaving food in the danger zone allow bacteria to multiply. CDC data show many outbreaks involve foods held at unsafe temperatures. Always cook food rapidly and keep cold foods refrigerated. Clean utensils and equipment thoroughly. Proper time/temperature control and hygiene prevent most bacterial proliferation.

Cross-contamination

Transferring pathogens from raw to ready-to-eat items is a major culprit. CDC reports that cross-contact (e.g., using the same cutting board for raw poultry and salad) factored in about 20% of outbreaks. Use separate utensils, change gloves between tasks, and sanitize surfaces after handling raw meats. Color-coded cutting boards or physical separation (raw meat area vs RTE area) are best practices.

Inadequate cooking

Pathogens survive if foods aren’t cooked thoroughly. Improper cooking is a top contributing factor in outbreak investigations. Always use a calibrated thermometer and follow safe minimum temperatures (e.g., 165°F for poultry, 160°F for ground beef). Sous-vide or slow-cook processes need strict controls. Enforcing proper cooking protocols ensures bacteria like Salmonella, E. coli, and Campylobacter are killed.

Poor personal hygiene

Food workers can be a hidden source. If an ill employee contaminates food or surfaces, viruses and bacteria can spread quickly. Studies suggest many norovirus outbreaks stem from infected food handlers. Train staff to wash hands thoroughly (after restroom breaks, coughing) and never handle food when ill. Use gloves or utensils for ready-to-eat items. Strict hygiene policies (and enforcement) block person-to-food transmission.

Contaminated water sources

Water used in growing, processing, or cleaning can carry pathogens. Outbreaks have been traced to contaminated irrigation water on farms and to improper washing or ice water in plants. Always use potable water for washing produce, making ice, or cleaning equipment. If using well or surface water, test it regularly or filter/sterilize it. Preventing waterborne contamination at the start keeps pathogens out of your raw materials.

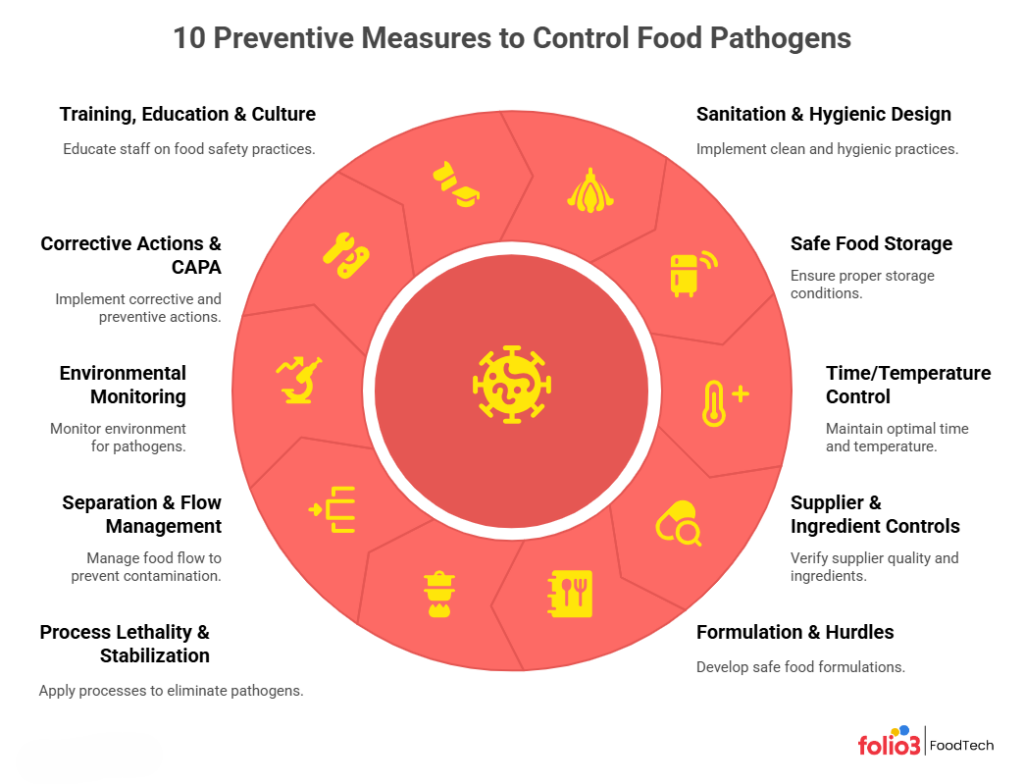

Preventive Measures and Best Practices to Outsmart Food Pathogens

Proactive controls are your most vigorous defense. Implement these strategies to make contamination nearly impossible:

1. Sanitation & Hygienic Design

Design equipment and facilities for easy cleaning (smooth, sealed surfaces). Include sealed drains and rounded corners, and use clean-in-place (CIP) systems where possible. Keep cleaning tools accessible and train staff on sanitation procedures. A thorough cleaning program prevents pathogen harborage.

2. Safe Food Storage

Store perishable foods promptly at ≤40°F (freezing for long-term storage). Label and rotate stock (FIFO). Keep raw meats separate (e.g., on bottom shelves) from ready-to-eat items to avoid cross-contamination. Use sealed, sanitized containers and pest-proof storage. Proper storage conditions and organization minimize microbial growth and contamination.

3. Time/Temperature Control

Enforce strict cooking and cooling rules. Cook proteins to safe minimums (e.g., 165°F for poultry) with calibrated thermometers. Cool cooked foods from 135°F to 70°F within 2 hours and then to 41°F within four more hours (use blast chillers or ice baths if needed). Record all times and temperatures. These controls ensure pathogens are either killed by heat or cannot multiply.

4. Supplier & Ingredient Controls

Vet and audit all suppliers. Require safety certifications (GMP, HACCP, FSMA) and lab tests for critical ingredients. On delivery, verify temperature, packaging integrity, and documentation. Maintain a list of approved vendors and conduct periodic audits. For high-risk items (eggs, spices, dairy), certificates of analysis are required. A strict supplier program keeps contaminated raw materials out of your plant.

5. Formulation & Hurdles

Incorporate intrinsic barriers in product design. Lower pH (with vinegar, citrus) or reduce water activity (with salt, drying). Add safe preservatives or cultures where appropriate. Ensure packaging supports these hurdles (e.g., vacuum packaging after adding cure). For example, pickled vegetables (acid + salt) and cured meats (salt + nitrite) rely on multiple hurdles. Monitor finished product pH and moisture routinely. Layering hurdles makes food inhospitable to pathogens.

6. Process Lethality & Stabilization

Build validated kill steps into your process. Use pasteurization, retorting, high-pressure processing, or other methods to eliminate microbes in raw ingredients or finished products. Calibrate equipment and monitor processes (time-temperature logs or biological indicators). Perform regular validation (e.g., microbial challenge tests) to confirm lethality (for example, a 12-log reduction in canned goods). A robust kill-step dramatically lowers initial contamination in the finished product.

7. Separation & Flow Management

Physically separate raw material areas from finished-product zones. Use different lines or rooms for raw vs. cooked products. Color-code equipment and PPE by zone, and require staff to change attire/clean hands when moving between zones. Maintain a one-way workflow (raw→cook→package). Also, separate allergen handling areas. Clear zone markings, barriers, and unidirectional flow reduce the chance of cross-contamination or backflow.

8. Environmental Monitoring (EM)

Implement a targeted swabbing program. Divide the plant into zones and swab food-contact surfaces (especially in RTE areas) regularly for pathogens (like Listeria or generic indicators). Track results over time – repeat positives indicate an issue. Use trend analysis or heat maps to spot hotspots. If a site tests positive, immediately clean and re-test. This proactive monitoring catches hidden contamination before it reaches the product.

9. Corrective Actions & CAPA

Use a formal CAPA (Corrective Action/Preventive Action) system. Document every deviation, test failure, or customer complaint. Perform root-cause analysis (e.g, “5 Whys” or fishbone diagrams) and implement fixes (equipment repair, retraining, procedure changes). Verify that the fix works and update SOPs accordingly. Track all CAPAs through closure. Involve cross-functional teams to ensure thorough solutions. A strong CAPA process ensures problems are fully resolved and not repeated.

10. Training, Education & Culture

Educate and empower your team. Train all staff (from line workers to management) on food safety basics (handwashing, sanitation, allergen control) and on your specific procedures (HACCP steps, SSOPs, GMPs). Use engaging, interactive training to test understanding. Emphasize accountability and maintain records of certifications. Conduct mock recalls and internal audits regularly. Reward good practices and encourage hazard reporting. A culture of food safety, where everyone feels responsible, is your best safeguard.

Real-World Examples of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

Learning from past foodborne illness outbreaks gives you practical insight into how pathogens can slip through the supply chain. By studying real-world examples, you can identify weak points, strengthen your controls, and prevent similar risks in your own operations.

Listeria in Cantaloupe (2011)

A Listeria outbreak linked to cantaloupe sickened 84 people in 19 states (15 died). Investigators traced the strain to a Colorado farm with poor sanitation. It was the first U.S. Listeria outbreak tied to melons, illustrating that even produce like cantaloupe can harbor deadly pathogens.

E. coli O157:H7 in Romaine (2018)

In late 2018, 62 people across 16 states were infected by E. coli O157:H7 in bagged romaine lettuce; 25 were hospitalized (none died). The FDA found the outbreak strain in irrigation water on a California lettuce farm, showing how contamination at the farm level can reach consumers despite no cooking step for salads.

How to Avoid Pathogens Using a Food Safety Software

In today’s fast-paced food industry, manual processes are no longer sufficient to ensure food safety. Digital tools like Folio3 FoodTech’s Food Safety Software offer a comprehensive solution to automate and streamline food safety management, significantly reducing the risk of pathogen contamination.

Our solution provides a suite of features designed to enhance efficiency and compliance:

- Automated HACCP Plans: Create and monitor Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans in real-time, ensuring critical control measures are consistently met.

- Real-Time Temperature Monitoring: Utilize IoT-enabled sensors to monitor and record temperatures with complete food traceability, ensuring that food is stored and transported within safe temperature ranges.

- Digital Checklists and SOPs: Replace paper-based systems with digital checklists and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), ensuring tasks are completed accurately and on time.

- Supplier Management: Digitize supplier onboarding and monitoring processes, ensuring that all suppliers meet safety and quality standards.

- Compliance Tracking: Stay audit-ready with automated tracking of compliance requirements, reducing the risk of non-compliance.

These digital tools streamline your workflow and plug potential gaps. By leveraging our suite, you create a proactive food safety culture, catching minor issues before they become significant outbreaks.

Conclusion: Ensuring Food Safety in a Globalized World

In today’s global food supply, vigilance is non-negotiable. Strict sanitation, temperature control, and continuous monitoring form a robust defense against pathogens. Training your team and leveraging technology helps catch issues early. Even a minor lapse can lead to contamination, so consistency is vital. The strategies covered here align with FSMA/GFSI requirements, protecting consumers and your brand’s reputation.

Connect with our foodtech experts or book a demo of our food safety suite to see how it can help you implement these strategies and stay audit-ready.

FAQs

How Often Should We Swab for Listeria in an RTE Environment?

In an RTE environment, swabbing for Listeria should be done at least weekly or bi-weekly, focusing on high-risk areas like food contact surfaces, drains, and equipment. The frequency depends on the facility’s risk level and previous results.

What’s the Fastest Way to Improve EM Hit Rates Without Shutting the Line?

The fastest way to improve EM hit rates is by enhancing sanitation practices, focusing on high-risk areas, and training staff on proper hygiene. Rapid testing methods also allow for quicker detection without halting production.

How Do We Decide Between Dry Cleaning and Wet Cleaning in a Dry Facility?

Choose dry cleaning for dust or light debris, and wet cleaning for grease, organic matter, or when thorough disinfection is needed. The choice depends on the type of residue and contamination risk.

What Documentation Do Auditors Usually Ask for During a Pathogen-Focused Inspection?

Auditors typically request HACCP plans, sanitation records, environmental monitoring results, corrective action logs, training records, and pathogen testing data to verify food safety compliance.