Each year, roughly 48 million Americans (1 in 6) fall ill from foodborne disease, with over 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. These largely preventable illnesses prompted the U.S. Congress to pass sweeping food-safety legislation. The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), signed into law by President Obama on January 4, 2011, represents the most significant overhaul of U.S. food-safety law since the 1930s.

The law was born out of the need to address several high-profile foodborne illness outbreaks (such as the 2006 spinach E. coli outbreak) and concerns about bioterrorism. FSMA shifts the focus from reacting to outbreaks toward preventing them. In practice, FSMA gives the FDA new authority to require preventive controls, hazard analyses, traceability, and inspections across the entire supply chain from farms and processors to shippers and importers.

So, FSMA is a game-changing regulation that impacts food manufacturers, processors, importers, and distributors. In this guide, you’ll get a step-by-step roadmap to FSMA, from discussing its seven core FSMA rules to a practical FSMA compliance checklist that will help you stay compliant with auditory events while sustaining your production without any risks.

What is FSMA? Origins, Purpose & Scope

FSMA stands for the Food Safety Modernization Act. It amends the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and gives the FDA broad new powers to oversee food safety. Congress enacted FSMA in December 2010, and President Obama signed it on January 4, 2011. FSMA covers any food (human or animal) regulated by the FDA, a share of the U.S. food supply estimated at 78% (the rest is mainly USDA-regulated meat, poultry, and eggs). In short, if your facility manufactures, processes, packs, or holds FDA-regulated food for U.S. consumers, FSMA likely applies to you.

FSMA’s purpose is preventive. Before FSMA, the FDA’s food safety focused largely on responding to outbreaks. Under FSMA, the FDA now mandates risk-based preventive controls. As the FDA notes, FSMA “is transforming the nation’s food safety system by shifting the focus from responding to foodborne illness to preventing it”.

Purpose & Key Strategies

FSMA’s core strategies can be summarized as:

- Preventive controls: Require all food businesses to conduct hazard analysis and implement risk-based controls (e.g., HACCP-like measures for processing, allergen controls, sanitation).

- Inspection & Compliance: Mandate a risk-based inspection schedule. High-risk domestic food facilities must be inspected at least once per year, and importers as often as foreign plants. The FDA now has the authority to access records and suspend facilities that don’t comply.

- Response/Recall: Give the FDA mandatory recall power for unsafe foods, plus detention and suspension authority to stop contaminated food from reaching consumers.

- Import Safety: Require U.S. importers to verify foreign suppliers (FSVP), and create voluntary programs (Accredited Third-Party, VQIP) so importers can expedite entry or certify foreign facilities.

- Partnerships & Training: Strengthen training and collaboration with state/local agencies and foreign governments to enforce FSMA requirements across jurisdictions.

Scope

Who must comply with FSMA? In general, all FDA-regulated food facilities (domestic or foreign) are covered, unless a specific exemption applies. It includes manufacturers, processors, and even some farms and transporters. For example, farms with sales over $25,000 and produce that is commonly eaten raw must follow the Produce Safety Rule. Facilities that register under section 415 of the FD&C Act are required to maintain FSMA food safety plans and preventive controls.

FSMA does not apply to USDA-regulated meat, poultry, and eggs, nor to tiny businesses under certain thresholds (special “qualified facility” provisions). So, if you handle FDA-covered food or animal feed intended for the U.S. market, you need to comply with FSMA requirements.

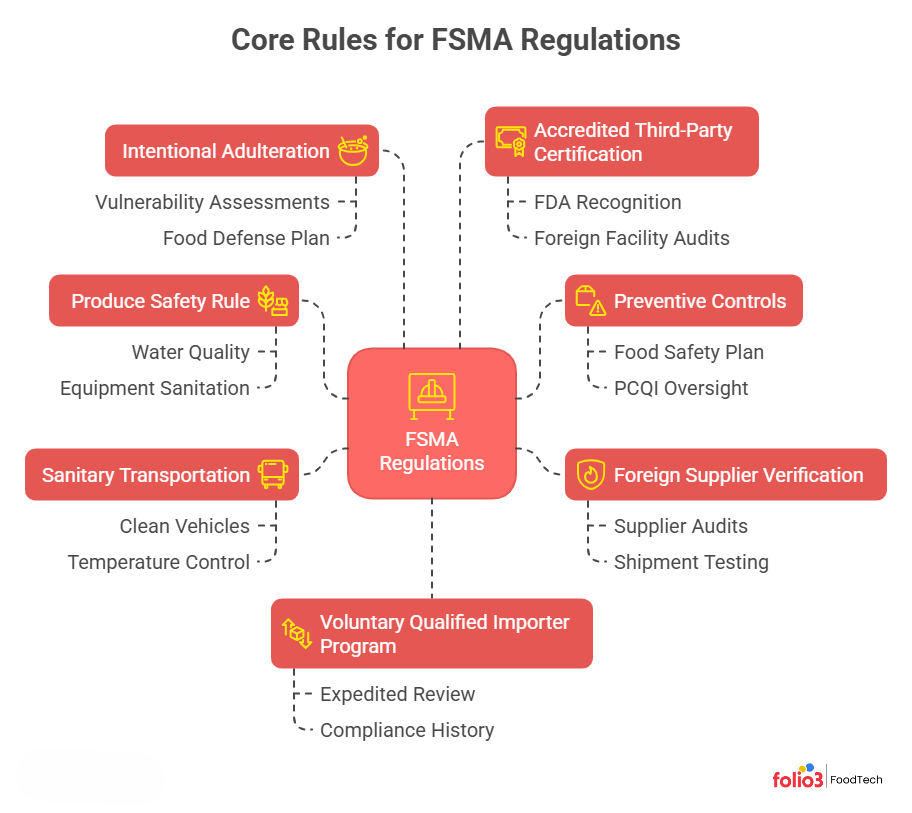

FSMA Regulations – Core Rules Explained

The FSMA regulations establish critical food safety standards for food manufacturers, ensuring preventive measures are in place to minimize risks. Explore the core 7 FSMA rules that every food processor must follow, from hazard analysis and preventive controls to traceability and transportation safety.

1. Produce Safety Rule

Sets out hygiene standards for growing, harvesting, and handling produce (fruits, vegetables, sprouts) to reduce microbial contamination. Farms must implement controls for water quality, equipment sanitation, worker health/hygiene, and compost/manure use. Covered farms generally have significant produce sales.

2. Preventive Controls for Human & Animal Food

Requires human food manufacturers to develop a written Food Safety Plan. This plan must list all known or reasonably foreseeable hazards (biological, chemical, physical) and specify preventive controls to minimize those hazards. The plan also details monitoring procedures, corrective actions, and verification steps. A qualified individual (PCQI) must oversee the plan’s preparation.

Similar to the human food rule, this mandates animal food/feed facilities (including pet food, livestock feed, grain elevators, etc.) to implement hazard analysis and appropriate preventive controls (e.g., ingredient testing, processing controls).

3. Foreign Supplier Verification Programs (FSVP)

Requires U.S. importers to verify that their foreign suppliers have adequate food safety controls. Importers must evaluate the hazard risk posed by each food/ supplier and establish a verification plan – for example, by conducting supplier audits, sampling/testing shipments, or reviewing supplier certifications. The aim is to ensure imported foods meet U.S. safety standards.

4. Sanitary Transportation Rule

Requires all parties (shippers, loaders, carriers, receivers) in food transport (by road or rail) to use sanitary practices. Shippers and loaders must ensure vehicles are clean and suitable (e.g., temperature-controlled), and carriers must maintain hygienic conditions during transport. This closes gaps exposed by past recalls, where unsanitary trucks or poor temperature control led to food contamination.

5. Intentional Adulteration Rule (Food Defense)

Requires covered facilities to conduct vulnerability assessments and implement mitigation strategies focused on preventing deliberate contamination intended to cause widespread harm (including terrorism). Each facility must identify vulnerable points (e.g., bulk liquid storage) and develop procedures (the “Food Defense Plan”) for monitoring and responding to suspicious activities. This is a new requirement under FSMA.

6. Accredited Third-Party Certification

Establishes a voluntary accreditation program for third-party auditors. An FDA-recognized accreditation body can accredit certification bodies (auditors), who in turn can audit foreign food facilities and issue certificates. These certifications can help importers qualify for VQIP (see below) or be used if the FDA requires certification for certain imports.

7. Voluntary Qualified Importer Program (VQIP)

A fast-track import program. Importers who demonstrate high levels of supply-chain oversight can pay a fee to participate. VQIP importers get expedited review of their imported foods, helping them bypass longer FDA import holds. To qualify, importers must meet stringent criteria (robust QA program, compliance history, current supplier certifications, etc.).

Additional Rules

FSMA recently included two additional rules that you must know:

Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods (LAAF)

This FSMA rule establishes a program to accredit food-testing laboratories. The FDA will recognize accreditation bodies to accredit labs to uniform standards. In some instances, like testing to remove an import alert or re-testing detained food, the FDA requires the use of an accredited lab. The goal is to improve the reliability and consistency of food testing (import and outbreak testing) by ensuring labs meet high standards.

Food Traceability Rule (FSMA 204)

Under FDA authority (FSMA section 204), the final Food Traceability Rule establishes additional recordkeeping requirements for “high-risk” foods on the Food Traceability List. Covered businesses at defined Critical Tracking Events, and provide them within 24 hours to the FDA if requested. The purpose is to enable rapid tracing of contaminated foods so that tainted products can be quickly identified and recalled, reducing illnesses and harm. It applies to domestic and foreign firms handling foods like leafy greens, fresh-cut fruits, cheeses, nut butters, and shell eggs.

FSMA Certification vs FSMA Compliance

What is FSMA certification? You may have heard the term “FSMA certification”, but it’s important to clarify that FSMA itself does not issue a formal certificate of compliance like ISO or GFSI schemes do. Instead, FSMA compliance is verified through FDA inspections or voluntary third-party audits. In fact, the only certification program in FSMA is the Accredited Third-Party Certification program, which accredits auditors to certify foreign facilities. I

A “FSMA compliance statement” (often requested by customers or retailers) is a document you may issue that lists which FSMA rules and programs you have in place (for example, noting that you maintain a PCQI-based safety plan, have a traceability system, etc.). While not a legal certificate, such a statement shows you have taken the necessary steps to comply with FSMA.

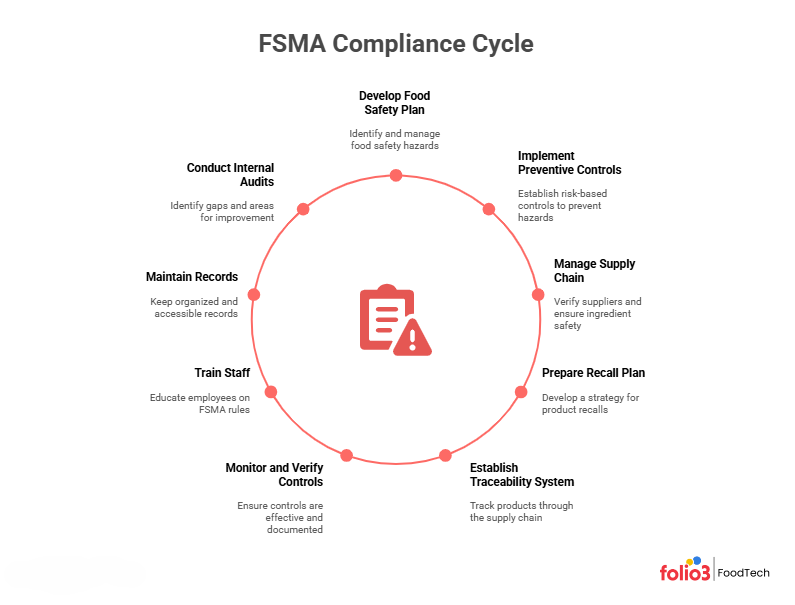

FSMA Compliance Checklist

To become FSMA-compliant, you should follow a roadmap of key steps. Below is a checklist of the essential components every FSMA-regulated business needs:

Food Safety Plan (Hazard Analysis)

Develop a written food safety plan that identifies all food safety hazards (biological, chemical, physical, allergen, etc.) that are reasonably likely to occur. This hazard analysis is the foundation of your FSMA compliance. The plan should document how you will manage each hazard.

Preventive & Corrective Controls

Based on your hazard analysis, establish risk-based preventive controls to prevent hazards from occurring (e.g., cooking or pasteurization steps, pathogen controls, allergen controls, sanitation, supplier controls). Also define corrective action procedures: what to do when a control limit is breached or a hazard is detected. For example, if a pathogen test fails, your corrective action plan might specify discarding the product, reprocessing, or re-evaluating the process.

Supply-Chain Program

If you rely on suppliers (ingredients or raw materials), implement a supplier verification program. For instance, the human food Preventive Controls rule requires a “supply-chain-applied” control if an incoming ingredient controls a hazard. This may involve supplier approvals, audits, incoming testing, or requiring your suppliers to have their own safety plans.

Recall Plan

Although FSMA does not explicitly require a recall management plan, the FDA was given mandatory recall authority under FSMA. It’s therefore good practice and often needed by retailers to have a written recall strategy. This should detail how you will notify customers and regulators and remove the affected product if a hazard is discovered. Being prepared with a recall plan can greatly reduce harm and financial loss in a crisis.

Traceability System

Implement a traceability plan, especially if you handle products on the FSMA Food Traceability List. Keep track of critical tracking events (e.g., harvest, receipt, production, shipping) and key data (lot numbers, sources, quantities). FSMA’s 204 rule requires records of traceability data for high-risk foods. In practice, this means knowing the “one up, one back” chain of custody so you can rapidly trace any contaminated batch.

Monitoring & Verification

For each preventive control, establish monitoring procedures (e.g., temperature logs, visual inspections, tests) to ensure controls are implemented. Similarly, set verification activities, such as reviewing records, calibrating instruments, or doing product/environmental tests, to confirm controls are effective. All monitoring and verification must be documented (with date, time, operator, and result). Regularly reviewing this data helps catch problems early and ensures controls are working.

Training & PCQI

Designate one or more Preventive Controls Qualified Individuals (PCQIs), people who have received FSMA preventive controls training or have equivalent experience. The PCQI is responsible for developing and overseeing your food safety plan. Ensure all staff are trained on the FSMA rules relevant to their jobs (e.g., sanitation crew, quality team, line supervisors, procurement). Well-trained employees are critical; lack of training is a common audit finding.

Recordkeeping (Electronic Allowed)

Keep all FSMA records in an organized manner. It includes your hazard analysis, safety plans, monitoring logs, corrective action records, supplier verifications, calibration logs, etc. FSMA allows the use of electronic records (per 21 CFR Part 11) as long as they are accurate and accessible. Many companies now use digital systems or compliance software to manage these records and make audits easier.

Continuous Improvement

Treat FSMA compliance as a cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act). Regularly review and update your food safety plan as you identify new hazards or process changes. Conduct internal audits or mock FDA inspections to find gaps. Use corrective/preventive action (CAPA) processes to learn from incidents and improve. The goal is not a one-time fix but an ongoing commitment to food safety.

Building a FSMA Food Safety Plan

A central requirement of FSMA (for most facilities) is a written Food Safety Plan. This plan must be created, or its preparation overseen, by a trained Preventive Controls Qualified Individual (PCQI). The plan should systematically describe how your facility manages food safety. The core elements of an FSMA-compliant food safety plan typically include:

- Risk Identification: List all steps in your food process and identify potential hazards (biological, chemical, physical or allergen hazards) at each step, as well as those introduced by raw materials or the environment.

- Hazard Analysis: Analyze each identified hazard to determine its severity and likelihood. Decide which hazards are “reasonably likely to occur” and therefore require control. Less likely hazards might be noted but not require controls.

- Preventive Controls: For each hazard needing control, specify a preventive control. This might include a CCP-like process step, an allergen control, a sanitation control, or a supply-chain control (e.g., approved supplier lists).

- Monitoring Procedures: Define how you will monitor each control. For example, record cooking temperatures, check sanitizer levels, inspect seals, or test lots of ingredients. Monitoring ensures that the control is actually being applied as planned.

- Corrective Actions: For any instance where monitoring shows a control step has failed (for example, a cold spot in cooking, or an out-of-range pH), specify what to do. This might include segregating or discarding affected product, correcting the equipment fault, retraining staff, or revising the process.

- Verification Process: Describe how you will verify that your preventive controls and monitoring are effective. Verification can include things like reviewing records periodically, performing environmental or product testing, calibrating thermometers, or even conducting mock recalls. The PCQI should review all records regularly to confirm compliance.

- Documentation: Describe how all of the above will be documented and kept. This includes the food safety plan itself, any validation studies (e.g., verifying a kill-step), monitoring logs, corrective action records, training records, and verification results. Good documentation is mandatory; FDA inspectors will expect to see dated records showing that you implemented and followed your plan.

FSMA Inspections & Audits

Under FSMA, the FDA’s inspection authority was significantly strengthened. FDA now mandates that high-risk domestic food facilities be inspected annually (and foreign facilities at similar frequencies). The FDA also enhanced surveillance and outbreak-investigation capability. In practice, your facility could be inspected under several triggers:

- Routine risk-based schedule (the FDA maintains an inspection priority list).

- In response to a foodborne illness outbreak or traceback to your product.

- As part of import verification (e.g. import alerts) or new facility registration.

- After receiving a specific complaint or report (e.g., from a supplier or customer).

When FDA auditors arrive, they will examine whether you have complied with FSMA requirements. In particular, inspectors will look for:

- A current Food Safety Plan and hazard analysis.

- Records of preventive controls (monitoring logs, sanitation checks, maintenance records).

- Documentation of corrective actions taken when deviations occurred.

- Verification records (tests, calibrations, internal audit reports).

- Evidence that a qualified PCQI has been assigned to oversee the plan (training certificates, name in records).

- Your supplier-verification or supply-chain program documentation (approved supplier lists, audit reports, etc.).

- Recall and traceability records (proof that you can track lots forward/backward).

Basically, auditors want to see the same bullets from the compliance checklist implemented and documented. For example, they may review temperature logs to ensure cooking or refrigeration controls were followed, check training records, or test that recalled-lot traceability works as claimed.

Common Pitfalls & How to Avoid Them

Even with the best intentions, many companies run into avoidable problems during FSMA audits. Common compliance issues include:

- Weak or Missing Documentation. Failing to record monitoring or corrective actions is a red flag. Ensure every step (temperatures, cleaning, testing, etc.) is logged. Tip: use checklists or digital logs so nothing is skipped.

- Poor Training and Awareness. If staff aren’t trained on FSMA basics, they won’t follow the plan correctly. All employees should understand their role in the food safety plan (e.g., how to record a CCP measurement or when to escalate an issue). Consider regular FSMA training refreshers.

- Overlooking the Supply Chain. Don’t forget hazards controlled by your suppliers. If you assume “the supplier handled it,” auditors will ask for your supplier program. Maintain records of supplier approvals, certificates, and any incoming testing you do.

- Not Updating for New Requirements. FSMA rules have evolved (e.g. FSMA 204 traceability is new). Stay current on FSMA developments and update your plan accordingly. For instance, implement the extra traceability data for foods on the new Food Traceability List.

- No Mock Audits. It’s risky to only scramble before an actual FDA visit. Instead, conduct your own internal audits or bring in a consultant to simulate an inspection. This will reveal gaps in your documentation or training well ahead of time.

By addressing these areas proactively, you minimize surprises during a real inspection. Remember: auditors are looking for proof that you have implemented your food safety plan, not just a plan on a shelf. Proper documentation, training, and review processes are your best defenses against FSMA audit failures.

Benefits of FSMA Certification for Food Processors

Investing in FSMA compliance brings clear advantages for food processors to stay compliant with regulations while increasing profit margins:

Enhances Food Safety and Consumer Trust

When you rigorously follow FSMA’s preventive approach, you reduce the likelihood of foodborne illness linked to your products – and that strengthens your brand. Retailers and consumers feel more confident buying from a company with documented FSMA processes.

Reduces the Risk of Costly Recall

A recalled product can cost millions and erode customer loyalty. Under FSMA, because you are continuously monitoring hazards and traceability, you can catch problems early and recall precisely, limiting scope and cost. In contrast, non-compliance can result in extended recalls, fines, or lost contracts.

Smooths Trade and Market Access

U.S. retailers and importers typically require FSMA compliance (or equivalent standards) of their suppliers. Having a recognized compliance program (or third-party certification) makes it easier to sell to U.S. distributors. For exporters, aligning with FSMA can also facilitate entry into other markets that recognize FDA standards or look for strong food safety systems.

Global Alignment with Food Safety Norms

Many of FSMA’s requirements mirror international benchmarks (such as Codex HACCP principles) and other countries’ regulations. By meeting FSMA, you are on par with leading global hygiene regulations, which can simplify meeting foreign audits. In short, a robust FSMA system not only protects public health but also protects your business’s reputation and bottom line.

Stay Compliant by Deploying an FSMA Compliance Software

Managing FSMA’s many records and workflows by hand is daunting. This is where digital solutions can help. By using an FSMA compliance software, you can have confidence that your FSMA compliance requirements are tracked and managed automatically, freeing you to focus on production while the software helps keep you audit-ready.

One solution that incorporates all these features is Folio3 Foodtech’s FSMA Compliance Management Software. This platform is designed for food and beverage manufacturers, and it bundles food safety planning, HACCP/compliance modules, electronic monitoring logs, and traceability tools into one system.

Key features to look for in an FSMA compliance software include:

- Hazard Analysis & Plan Builder: Tools or templates to develop your food safety plan (HACCP/PC rules).

Document Control: Central repository for FSMA documents (plans, SOPs, certificates) with version control. - Monitoring & Alerts: Ability to log monitoring data (e.g., temperatures, pH) in real time, with alerts if values deviate.

- Supplier Management: Track supplier approvals, audit certificates, and any needed FSVP or foreign audits.

- Traceability & Recall: Lot-level tracking from receiving to shipping; automated recall simulations and response planning.

- Audit Checklists: Mobile-friendly audit or inspection checklists tied to FSMA rules, with corrective action tracking.

- Training & Compliance: Assign and track employee training (e.g., PCQI training); ensure employees acknowledge procedures.

Reporting & Analytics: Dashboards showing compliance status (e.g., overdue tasks, upcoming expirations) and custom reports for regulators.

FAQs

What is the Difference between HACCP and FSMA?

HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point) is a voluntary system for identifying and controlling hazards in food production. FSMA (Food Safety Modernization Act) is a mandatory U.S. law that builds on HACCP by requiring food processors to implement preventive controls, conduct hazard analysis, and maintain a Food Safety Plan. FSMA also mandates recordkeeping, inspections, and supply-chain verification, which HACCP does not.

How Can FSMA Compliance Impact Your Business?

FSMA compliance helps prevent foodborne illnesses, reduces the risk of recalls, and protects your brand’s reputation. It ensures that your business meets FDA standards, making it easier to secure partnerships with retailers and distributors. Non-compliance can result in fines, recalls, and supply chain disruptions, affecting your bottom line.

How Often Do FSMA Inspections Happen?

High-risk facilities are inspected annually. Low-risk facilities may face inspections less frequently, depending on their classification. New facilities or those with past issues may be inspected sooner, and inspections can occur unannounced.

What is the Role of a PCQI in FSMA Compliance?

A PCQI (Preventive Controls Qualified Individual) is responsible for developing and overseeing the Food Safety Plan, ensuring preventive controls are implemented, and maintaining compliance with FSMA regulations. They provide monitoring, corrective actions, and recordkeeping are correctly managed.

How Can I Ensure FSMA Compliance for My Food Processing Facility?

To ensure FSMA compliance, develop a Food Safety Plan with hazard analysis and preventive controls, implement monitoring and corrective actions, train staff, and keep thorough records. Use compliance software to automate traceability and documentation, and perform mock audits to stay prepared for inspections.